One of the most challenging types of metastatic cancer is leptomeningeal metastasis (LM). It occurs when cancer cells escape from a tumor originating in another part of the body — often the breast or lung — and spread to the fluid and tissues that surround the brain and spine. Once LM arises, most patients die within a few weeks or months.

How cancer cells can survive and grow in spinal fluid, where there are no nutrients to support their growth, has long been a mystery. But a team from Memorial Sloan Kettering set out to solve it. The researchers reported in the journal Cell that they have found that a certain protein allows the cancer cells to thrive in this barren zone. In addition, with the help of mouse models they created to study LM, they have already identified a drug strategy that may combat this largely untreatable condition.

“When cancer gets into this space, it’s devastating for patients,” says MSK researcher and neuro-oncologist Adrienne Boire, the study’s first author. “They have terrible symptoms,” including pain; seizures; difficulty thinking; and a loss of muscle, bowel, and bladder control.

Current treatment for LM is radiation therapy and chemotherapy, but neither is very effective. Spinal fluid often enables cancer to spread throughout the nervous system, making it a challenge to pinpoint specific spots for delivering radiation. And because of a barrier between the blood and the cerebrospinal fluid, it’s difficult for chemotherapy to reach the affected areas.

Dr. Boire’s motivation to study LM came from a patient. “I was treating a woman on the inpatient neurology floor whose breast cancer had spread to her spinal fluid. She had a lot of questions for me about why this was happening to her, and why there were not better treatments available,” Dr. Boire says. “When I realized I had no answers, I went right to the lab and got to work.”

That was three years ago. And she has learned a lot since then.

Uncovering an Explanation

Addressing a Devastating Complication of Cancer

In addition to being a clinician, Dr. Boire is a fellow in the lab of Sloan Kettering Institute Director Joan Massagué, whose research has focused for many years on the molecular underpinnings of cancer metastasis and who was senior author of the new study.

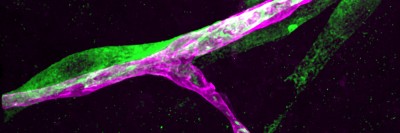

To figure out how certain cancer cells grow in spinal fluid, the investigators analyzed a number of cell lines of breast and lung cancer. They implanted the cell lines in mice and monitored them to determine which ones developed LM. Once they sorted out which cell lines were able to colonize spinal fluid, they set out to determine how the cells differed on a molecular basis.

To their surprise, they discovered what all the cell lines had in common was a protein that was already well known: complement component 3 (C3), which plays a role in the body’s response to infections.

“C3 is related to inflammation. It’s connected to the swelling that results when leakage of fluid occurs across membranes,” Dr. Boire explains. “We found that C3’s function in these cancer models is a variation of what it does as part of the normal immune response.”

Crashing the Gates

“Our research shows that C3 opens up the membrane between the blood and spinal fluid and allows some of the growth factors and other nutrients from the blood to get in,” she says. Once the barrier is open and the cancer cells are able to bring in what they need, this barren zone becomes more habitable.

To confirm that C3 was the key factor, the researchers investigated tumor cells removed from patients who had LM. All of them made the protein.

Once it was understood that C3 was causing the leaky membrane, the team looked for a way to plug the leak. They found it in a compound targeting C3 that was originally developed to treat asthma but ultimately wasn’t effective against that disease. The drug, however, did successfully suppress LM and slowed disease progression in mice. Now the researchers are investigating the possibility of using it to treat metastatic cancer in patients.

Addressing a Growing Clinical Priority

Between 5 and 10 percent of patients with solid tumors eventually will develop LM. In addition to being more common in people with breast and lung cancers, it’s also a frequent complication of melanoma.

“In the past, LM was part of the fatal end stage of cancer,” Dr. Boire says. Because patients at that point had so many other complications, not many efforts were focused on it. But, she notes, “now that patients are living longer and we’re able to treat other sites of metastasis, this is becoming a clinical problem that we need to learn how to address.”

The patient who inspired Dr. Boire’s research unfortunately has died, and Dr. Boire has treated many others with LM in the three years since she turned her attention to this problem. “I’m very excited about this research, and for people to learn more about it,” she says. “My patient asked me to just do a little bit of work, and I’ve been able to take this so far and do so much to understand LM.”